Maxine Sakai : LOST (2006-), Spiritual Furniture (1996-), and Objects (1996-), are all currently ongoing projects. What is your process for considering a found object’s inclusion in one of these installations?

Jane Brucker : My studio has a huge collection of objects, trinkets, family photos, hardware, wood, parts and pieces all organized into boxes and containers. I just moved into a new studio and am using some old drawers from the 1940’s that I found here to organize current items that interest me and that relate to new and ongoing projects. Usually my process involves handling and touching the objects to assess their meaning. I consider the history of the things I collect too, whether they were a part of my family or have meaning to others. Tiny objects that represent actual or symbolic things we lose during our lifetime and can be cast in metal using the lost-wax technique are considered for LOST. Other physical elements will suggest inclusion as a more singular sculptural work. Some can be combined with particular pieces of furniture in my studio too. Right now, I have two oak filing cabinets that have beautiful wood grain and are very old and falling apart. They were part of someone’s desk.

Maxine Sakai :What recurring themes do you hope audiences can resonate with when viewing these works?

Jane Brucker : Loss is a recurring theme in the work, and is already present in the objects I use because of age or condition. Contemplation of mortality and the fragile transience of life also seems to be a continual touchpoint.

Maxine Sakai : In 2019, Baik Art Gallery exhibited No Permanence is Ours featuring your ongoing installation and performance, Unravel, alongside the work of Park Chel Ho. Could you expand on the influences and meaning of this work?

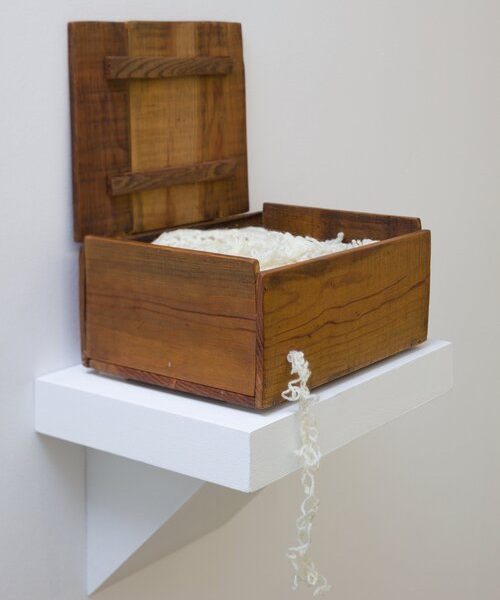

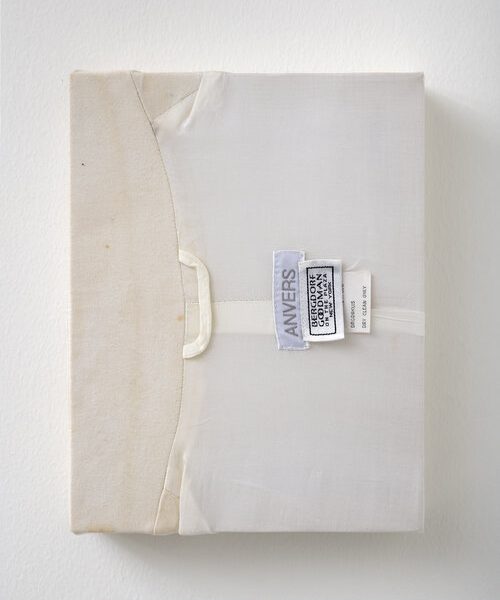

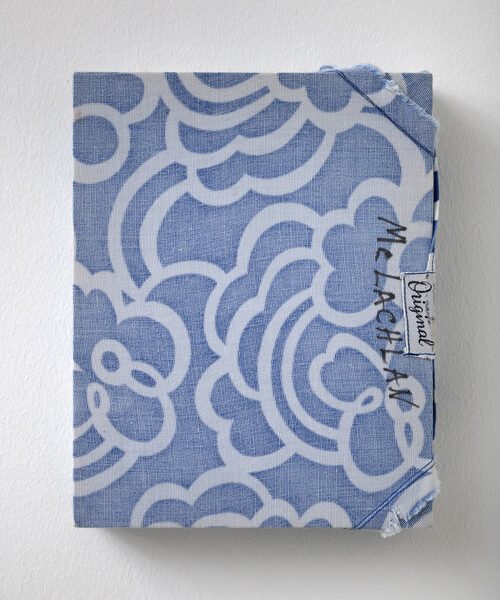

Jane Brucker : I loved getting the chance to meet Park Chel Ho and felt the textile-like surfaces and repetitive imagery of his paintings created a contemplative feeling that was very moving and reflective. The Unravel installation at Baik was also intended as a meditation on quiet and the activity of taking something apart. Hand-knit blankets, sweaters, shawls, and vests in various stages of undoing mirrored the compromise and change inherent in life. For the first time in the project’s 12 year history, the unraveled garments rest in wooden boxes that I created. The idea is that sometimes we also need somewhere to contain the experience of falling apart.

Maxine Sakai : As both a student and teacher of the Alexander Technique, how do you apply the method to your art practice?

Jane Brucker : The Alexander Technique is a subtle but powerful way of understanding how our body and mind are connected and wholly engaged in both activity and stillness. I always practice AT while working and resting. For example, renewing one’s awareness of ‘gravity and balance’ or ‘noticing tension and letting go’ is ongoing. You can apply it to any activity. I use it often when making my work, especially if I am using tools or making something that requires delicacy, patience and skill. Maybe that is how it became part of my performances too. I use it for myself but in Unravel project, I also teach it to others. Sometimes I teach it to workshop participants from the public who are invited to the experience of tension awareness and letting go by unraveling items together. In other settings, I teach it to a single performer or group of performers I collaborate with as choreographic direction and preparation for the performance.

Maxine Sakai : galerie PLUTO in Bonn/Cologne, Germany thrives at “the intersection of art and science.” Could you tell us more about PLUTO?

Jane Brucker : My husband, Dr. Jeremy Wasser, is a comparative physiologist and also teaches the history of medicine. A comparative physiologist examines the diversity that exists in various kinds of organisms and the environment, often in an adaptive and evolutionary context. He is also a musician, so for him, it makes sense to look at how we understand the natural world and relate to it through both science and the arts. With my own academic background in theology, as well as the interdisciplinarity of all of our colleagues, galerie PLUTO provides a creative platform for artists, posthumanists and scientists to be in conversation together in Bonn, Germany and now online. Together, we want to explore how science and art can help to solve the problem of climate change and the challenge of working in harmony with our natural environment.

Maxine Sakai : Currently, your installation Fragile Thoughts is exhibited in Judson Studios: Stained Glass from Gothic to Street Style at Forest Lawn Museum in LA County. How do you think Fragile Thoughts contributes to public consciousness in the COVID-19 era?

Jane Brucker : Thanks for asking this question. I made Fragile Thoughts in 2018 as a kind of portrait of Elizabeth Milbank Anderson, a rich heiress that became an activist for public health. She had a child die from diptheria and she survived the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic. She contributed greatly to the care of tuberculosis patients and the eventual cure for this disease. I found a connection also existed between my own great-grandfather who came to California because he had tuberculosis and David Judson’s great-great-grandfather, who had tuberculosis as well and went on to establish Judson Studios. Many people came to California to seek treatment for tuberculosis during the early 20th century. Anderson used her money and influence for social good. She saw the connection between poverty and healthcare and wanted to make the world a better place. The image of the two girls on the red glass chairs are illustrated from a photograph I found of the Milbank Public Baths in NYC in the Smithsonian Institution Archives. The bathhouse was built for the poor Irish, Jewish, and other immigrants that lived in cold water flats and had no access to warm bath water and adequate hygiene. That is why the girls are barefoot. In the photograph, the girls, from young toddlers to teens, are shown posing in the bathhouse dressed in their best clothes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted for all of us, world-wide, the disparity in access to healthcare among groups of people, especially the poor. It has exposed the differences in how societies think about and provide medical resources to their citizens. A new public understanding of these fundamental problems extends beyond the awareness of healthcare professionals and we are seeing an opening for governments and individuals to engage together in addressing these longstanding problems. Sadly, I think Anderson would be disappointed in how little progress has been made in this arena.

Maxine Sakai : Aside from your ongoing installations and current exhibition, are there any upcoming projects or collaborations you have been working on?

Jane Brucker : Given the loss so many people experienced during the last year, I have been receiving articles of clothing to be included in Memorial Project and am creating a new digital archive called Memorial Stories. I am compiling the stories associated with the articles of clothing that were donated to my ongoing work for the past 20 years, Memorial Project (2001-present). These narratives told in the words of the sender have always seemed as if they should be part of the larger piece.

LOST will be exhibited at the San Diego International Airport for one year beginning in July. It will be fun to have that project on exhibit in my hometown. Another collaboration with Judson Studios was completed for the Edward Kennedy Institute in Boston. I would love to continue to do more with glass, and am experimenting on some very small sculptural works using glass and heirloom objects in unique ways resembling bouquets.

ADDITIONAL CONTENT

FIVE

June 22 - August 10, 2019

NO PERMANENCE IS OURS

Jan 5 — Feb 2, 2019